If you’re considering seeking help in any area of your life, it probably has something to do with your emotions. Some clients have trouble understanding them, others have trouble expressing them; some are overwhelmed with them while others are burdened by the absence of them. What are emotions and why do we have them?

One of the reasons those questions are so important is because life change seems to depend on them. Across all theoretical approaches, the “common grammar” of each of them involves emotional regulation (Palmieri 2022). Emotions seem to be at the heart of why we do what we do, not just for the most expressive people, but for all people. The opposite of being “emotional” isn’t being “rational” – it’s being dead, unmotivated. Having human experiences is having emotional experiences. Emotions are so tied up with our thinking that moral psychologists tend to view them as primary, not secondary, aspects of cognition. Thinking and feeling come wrapped together. Underneath every emotion is a split-second, snapshot interpretation of the world (Roberts 1988). When the world seems dangerous or threatening, we feel fear or anxiety. When the world seems inviting and abundant, we feel joy. When the world seems unfair we feel anger. And so on. Of course we usually feel more than one thing at a time, which you might expect, since the world is a complicated place. But thinking about our emotions can help us to work backward to trace out a view of the world and how it relates to us. The thing to notice about that is that our emotions, unlike our conscious thinking, is more brutally honest about that interpretation. Our minds can tell us we’re safe until we’re blue in the brain, but our emotions tell us what we really think.

And this, obviously, is an incredibly important part of our relationships. Relationships are two sets of emotions, two interpretations of reality, crashing into one another. The emotional energy behind other people’s words and actions reflect their snapshot interpretations – and our emotional reactions to them are our split-second interpretations of those emotions. You can see how all of this moves so much faster than we can consciously think – which is why it shouldn’t be a surprise that we sometimes have trouble understanding not only the other person, but even our own reactions.

So let’s carve a little deeper. Where do these almost instantaneous reactions come from? Have you ever wondered why something made you so angry or what it was that suddenly turned you off about a person? Our emotions, like our thinking, have developed over time. They are programmed by our past experiences and kick in before we can consciously make up our minds about what we think, because that’s what it takes to keep us alive. You can imagine what might happen if you saw a ravenous bear rushing your way and you had to sit and ponder the oncoming threat. Your emotional reaction of fear and flight kick in immediately so that you don’t become dinner. Some of that is built in. But other parts of it are made up of your life experience – if you had delightful experiences of friendship and communion with bears your whole life, your fear response may have been conditioned away, causing you to hold out your arms for the hug you’re expecting.

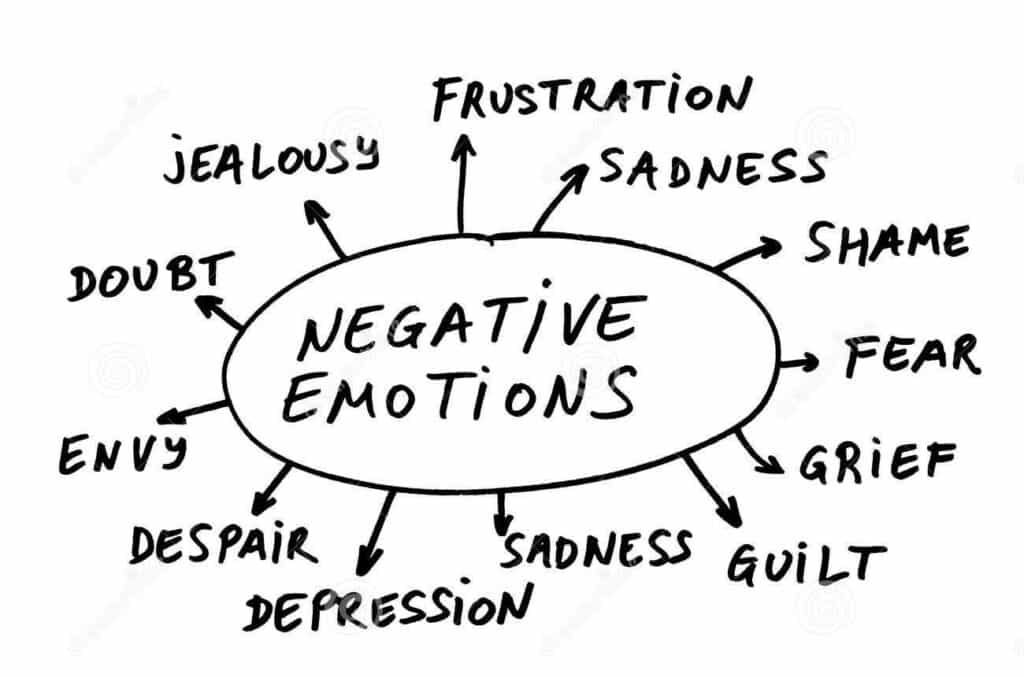

Our experiences with our first caregivers, the family environment we were raised in, the positive and negative experiences we’ve had throughout our lives, all help to program these instant reactions we have to our circumstances. We begin to play out these learned emotions, these survival strategies, including those snapshot judgments about the world, without thinking about them. They are unconscious and immediate, more like intuitions than carefully worked out thoughts. And yet they are made up of convictions, values, thoughts and the meaning we’ve made of life’s experiences to this point. Sometimes those emotional reactions become so embedded in our personalities that they form neurological habits – like anxiety and depressive disorders. And of course we make meanings out of those emotions too, as they inform our interpretations of ourselves and the world. These forces often shape us in ways contrary to our most deeply held values; we value peace but seem to feel constant conflict. We value love and relationship, but find ourselves feeling threatened and alone, etc.

So how do we change our emotions to become more adaptive in relationship, to better align with our values? We need a space where we can slow down, stand back from them and think about them. We need an environment where we can bring to mind the experiences that have taught our bodies how to respond to life, so that we might be able to understand our split-second reactions. We need to create new experiences of healthier emotions that retrain those reactions to better reflect our values (Subic-Wrana 2016). As we gather insight about our unconscious interpretations of the world, learn to tolerate and examine negative emotions and retrain our bodies to respond in more flexible and constructive ways, everything improves. And this is the work of therapy.

————————————————

Subic-Wrana C, Greenberg LS, Lane RD, Michal M, Wiltink J, Beutel ME. Affective Change in Psychodynamic Psychotherapy: Theoretical Models and Clinical Approaches to Changing Emotions. Journal of Psychosomatic Medicine Psychotherapy. 2016 Sep;62(3):207-23.

Palmieri A, Fernandez KC, Cariolato Y, Kleinbub JR, Salvatore S, Gross JJ. Emotion Regulation in Psychodynamic and Cognitive-Behavioural Therapy: An Integrative Perspective. Clinical Neuropsychiatry. 2022 Apr;19(2):103-113

Roberts, Robert C. What an Emotion Is: A Sketch. The Philosophical Review. 1988. Apr; 97(2): 183-209